MLB

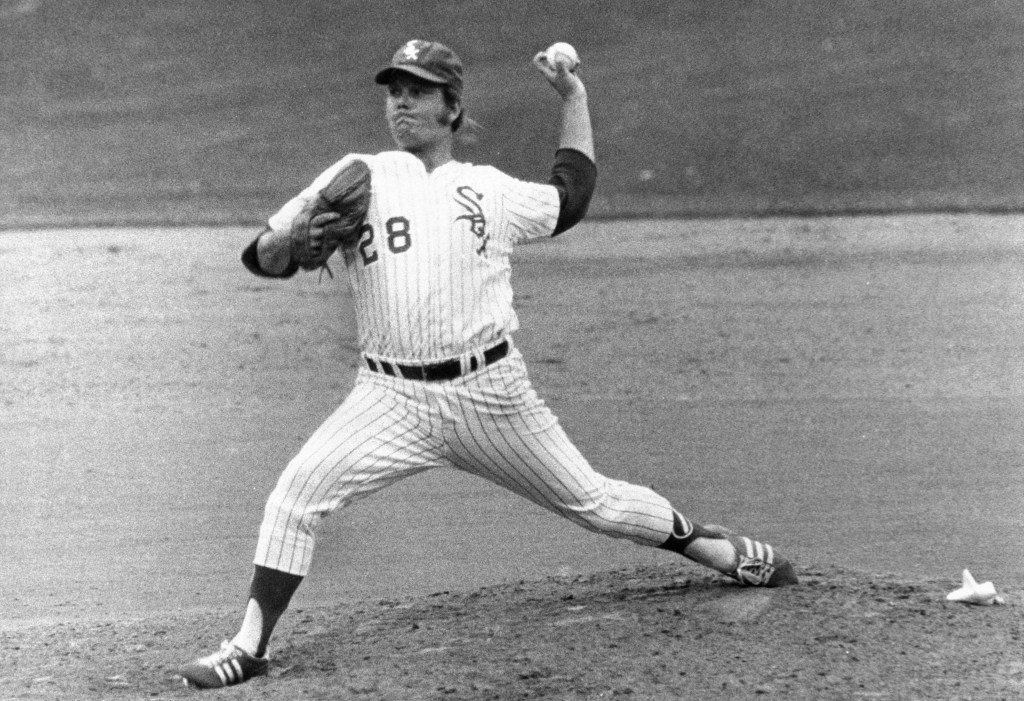

Wilbur Wood, the workhorse Chicago White Sox knuckleballer who had 4 straight 20-win seasons, dies at 84

Source

chicagotribune.com

Wilbur Wood, who became a Chicago White Sox legend thanks to his rubber-armed durability and a baffling knuckleball, died Saturday in Burlington, Mass., the New York Times reported. He was 84.

Wood’s wife, Janet, confirmed his death to the Times.

Wood pitched 17 seasons in the major leagues, the final 12 with the White Sox, and was a three-time American League All-Star. He finished his career with a 164-156 record, 114 complete games, 24 shutouts and 57 saves.

All three of his All-Star selections came in a four-year span (1971-74) with the Sox in which he won 20-plus games every season and twice led the majors in innings pitched. From 1971-75, he made an incredible 224 starts (44.8 per year).

Born on Oct. 22, 1941, in Cambridge, Mass., Wood pitched his Belmont High School team to back-to-back state championships in 1959 and 1960.

“He was a real hot-shot pitcher,” remembered Roland Hemond, the former Sox executive who then was a minor-league director for the Milwaukee Braves. “I first met Wilbur in 1960 when our scout Jeff Jones sent him to Milwaukee for a tryout right after he had graduated from high school. He was a fuzzy-faced, chubby little guy who didn’t throw very hard. I watched him throw batting practice but I couldn’t get very excited about him.

“After his workout I brought him up to the press room in County Stadium with my wife, and we fed him hot dogs. We did discover he had a good appetite. He was such a likable little guy, it was tough to tell him he didn’t throw hard enough and we weren’t interested.”

Wood could throw a knuckleball as a teenager, but he relied primarily on a more traditional repertoire of fastballs and curveballs. Even though his stuff was far from spectacular, the Boston Red Sox took a chance on the local kid and signed him to a minor-league contract.

“I picked up the knuckleball sort of by accident from my father when I was in junior high,” Wood explained. “He threw a hell of a palm ball in a semipro league in the Boston area. The palm ball, like the knuckleball, doesn’t rotate. I figured it must be a good pitch because Dad was making more money as a semipro than he was as a food broker.

“But I couldn’t throw the palm ball because my hand was too small. I just kept trying to throw a ball that wouldn’t spin. It turned out to be the knuckler. I never knew a damn thing about it — what kept it from rotating or how to control it — so I never used it. I wanted to stay around long enough to at least get a cup of coffee in the big leagues. I couldn’t afford to fool around with it.”

Wood made his major-league debut in 1961 with the Red Sox at 19. He earned brief promotions to Boston in each season through 1964 before being traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates, for whom he spent the 1965 season as a mediocre relief pitcher. He was demoted to Columbus the next season and traded to the White Sox on Oct. 12, 1966.

“I was lucky because when I came to the Sox, Hoyt Wilhelm was still with them — probably the greatest knuckleball pitcher of all,” Wood said. “He told me if I was going to throw the knuckleball, I should junk the rest of my pitches. I wasn’t doing any good with them anyway, so I took his advice. I had nothing to lose.”

The Sox mainly used Wood out of the bullpen at first, though he did make occasional starts. He had a breakout season in 1968, when he appeared in 88 games — most in the major leagues — and posted a 1.87 ERA. He led the AL in appearances in 1969 and 1970, regularly working multiple innings.

In 1971, the Sox made him a starter and his career took off. He went 22-13 with a 1.91 ERA and 210 strikeouts, then followed that with a league-high 24 wins in 1972 and 24 more to lead the majors in 1973 (when he also lost 20).

He went 20-19 in 1974, reaching the coveted 20-win plateau for the fourth straight season. Wood twice led the majors in innings pitched (376 2/3 in 1972 and 359 1/3 in 1973) and threw 300-plus innings four years in a row.

In Wood’s era, most teams went with a four-man rotation, giving pitchers a minimum of three days’ rest between assignments. By the 1990s, the standard had changed to a five-man rotation and four days’ rest.

But in 1972, Wood started 25 games on only two days’ rest, winning 12 and permitting fewer than two earned runs per game.

“(Pitching coach Johnny) Sain convinced Wilbur he could do it,” said the late Chuck Tanner, who managed Wood with the Sox. “When Sain was pitching for the Boston Braves, he once pitched nine complete games in 25 days. He asked Wilbur if he would like to try it. We felt it took less effort to throw a knuckleball exclusively.

“We came up with the theory that the more you throw the knuckleball, the better it gets. And a starting pitcher will throw a lot more pitches than a reliever.”

In May 1973, a game against Cleveland had to be suspended after 16 innings because of a curfew rule. When the game resumed the next day, Wood took the mound for the Sox and worked five innings, picking up the victory thanks to a walk-off homer by Dick Allen in the 21st off Ed Farmer, the future Sox broadcaster.

Wood then started the regularly scheduled game that followed, throwing a four-hit shutout.

Later that season, Wood started both games of a scheduled doubleheader against the Yankees in New York, the first pitcher to so since 1918. It was a bit of a fluke, however; Wood was knocked out of the opener in the first inning, giving up six runs and failing to record an out. After such light duty, he was available to start the second game but didn’t fare much better, giving up seven runs in four-plus innings. He was the losing pitcher in both games.

Wood’s success and durability made him a star, but “you’d never know it either by his actions or the way he looks,” Tanner told the Tribune in 1973.

Tanner described Wood’s appearance in the early ‘70s.

“He never shaves and he wears that baggy long underwear that’s cut off at the knees and one of those oversized sweatshirts that hangs over his belly, and his hair is getting thin and he always has a big cigar in his mouth,” Tanner said. “Well, one day he was tromping around like that and it happened to be the day his front tooth fell out.

“I had two friends from New Castle, Pa., my hometown, visiting me. They were walking through the clubhouse and I was introducing them to everybody and Wilbur came by. I said, ‘And this is Wilbur Wood.’ Well, they shook hands and just kept on walking like it was nothing. I stopped and asked, ‘What did it feel like to shake hands with the best left-handed pitcher in baseball?’

“’You mean that was Wilbur Wood?’ they asked. ‘We thought he was the janitor or the clubhouse man.’”

Wood’s last season with the Sox was 1978. He struggled in the second half and they shopped him around, hoping a contender might want him for a pennant drive. But Wood vetoed at least two possible trades when teams wouldn’t guarantee they would sign him for the following season. He finished the year with the Sox, posting a 10-10 record and a 5.20 ERA.

The Sox had seen enough and allowed Wood to become a free agent. The Cubs and Athletics showed some interest in the spring of 1979, but neither team would meet his salary demands.

“There’s nothing to say, I guess, except that I’ve had it,” Wood said. “This is it for me. I guess I have no choice but to retire.”

Even in the ‘70s, Wood was a throwback to an earlier era, relying on a gimmick pitch that wasn’t very common then and is now virtually obsolete. He also pitched whenever he was needed, for as long as he was needed. In his day, no one talked about pitch counts and no one dared to call a five-inning effort a “quality start.”

“When I see guys come out after five or six innings and hear someone say, ‘He had a hell of a game and gave it all he had,’ I get a little tired of that,” Wood told the Tribune’s David Haugh in 2005. “When I played, pitchers who went five and six innings were afraid of getting cut at the end of the year.”